Interview

Throughout her long career as a graphic designer and educator, the Ukrainian–American artist/designer Christine Zelinsky has maintained a lively professional exchange between America and Europe. In her roles as teacher and practitioner, she has investigated unique and transformative connections between art and design.

Born in Lviv, western Ukraine, her family immigrated from war-torn Europe to the US in 1949. They settled in Philadelphia, where Zelinsky studied illustration at Moore College of Art and Design and Ukrainian literature at the University of Pennsylvania from 1958 to 60. Searching for a more substantial visual education, she left for Europe and, while in Munich, encountered the German designer and close friend of Armin Hofmann, Michael Engelmann. This meeting would eventually lead her to study at the Allgemeine Gewerbeshule, Basel (now Hochschule für Nordwestschweiz), from 1961 to 66.

In 1967, Zelinsky took up a design position with the city of Kansas City, Missouri. At the same time, she also taught part-time at the Kansas City Art Institute, where she first met student April Greiman. She returned to Switzerland in 1969, and was employed by the advertising agency Erwin Halpern, in Zurich, until 1975. During this time, she also accompanied the experimental typographer Wolfgang Weingart as a translator on his first lecture tour in the US, between 1972 and 73. In 1977, after two years of freelancing in Zurich, Zelinsky accepted an invitation from the design faculty of the Philadelphia College of Art (now University of the Arts) to develop the drawing curriculum for their graphic design department , a position she maintained until her retirement in 2007.

Driven by her independent spirit, Zelinsky has been able to carve out a position for herself in an industry that, until recently, has been dominated by men. Balancing a Swiss design education at the Allgemeine Gewerbeschule Basel with strong influences from the world of fine art, her work has evolved in distinctive ways that continue to set her apart from her contemporaries and today’s practitioners alike.

Louise Paradis I was fascinated by your article in issue 3 of 1972 of Typographische Monatsblätter, partly because it was the first “TM Communication” article.

Christine Zelinsky It might not have been the first. On the cover you will see it says, “Number 3.” Wolfgang Weingart did a whole series of “TM Communication.” Before me there were two other people featured.

LP Was it Weingart’s idea to have you featured in TM?

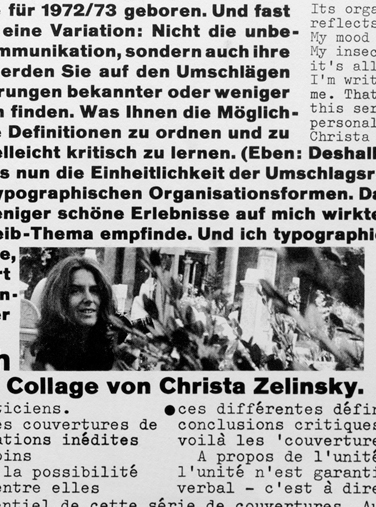

CZ Yes. We were good friends. I had just come back to Switzerland from Kansas City, where I had worked at the city hall as a designer. I did a double-spread collage for him, and that was the beginning of our collaboration.

LP Yes! I saw that. A great piece of work.

CZ My collage was published as a double-page spread, which was used as an introduction for the upcoming plan of the evolving “TM Communication” series. In the beginning, Weingart and I collaborated on the collage, but then he saw all my work from Kansas City, and asked if I would do an issue with Rudolf Hostettler [the editor of TM at the time]! I accepted the invitation. And I was—not to brag—the only woman designer in Switzerland at that time using the Pop art vernacular.

LP There were so few women in the field at the time. TM magazine, for example, was really a boys’ club.

CZ Yes, a boys’ club, indeed. Modernism as a whole was a boys’ club. It was full of dictates about what could and could not be done. It was used as the aesthetic podium from which we were all expected to work. But my influences came strongly from fine art: the American signal painters such as Al Held and Clyfford Still, the German painter Hans Hartung, and others. Held was especially influential in the development of my own vernacular, my own personal language. I had already started moving into the area of Pop art while at design school: Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg. Their work fascinated me. It pulsed at a different level.

LP Was Weingart your teacher at the Basel school?

CZ No. Weingart and I were both students at Basel at the same time. Yet he wasn’t very much of a student. He would come and go. He had his own schedule. He sometimes would do his projects in Emil Ruder’s class, but then Ruder fell ill.

LP Did Weingart take over the typography classes then?

CZ No. Weingart came later. I think Weingart began to teach in the Weiterbildungsklasse (International Advanced Program for Graphic Design, at the Schule für Gestaltung Basel). I believe that Armin Hofmann initiated this program in 1968. Hofmann invited Weingart to teach at the graduate level, so that’s how that collaboration began.

LP Are you American?

CZ Well, I am an American citizen, yes. But I was born in western Ukraine during the Second World War, in 1940. I belong to the “old girls,” the liberal women.

LP Were there many women in your classes in Basel?

CZ There were many, but it was a question of mentality—a different orientation or awareness. While I was reading Betty Friedan in the mid-60s, the other “girls” were all in the traditional mode of thinking. So we had little in common. It was a different sociopolitical situation: Switzerland was asleep compared to what was happening in the US. You know, there was the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights movement, and I felt very much a part of that. Being in Kansas City in 1968 as Robert Kennedy and Dr. Martin Luther King were assassinated woke us up! We experienced the social upheavals at close quarters. We had curfews; we experienced the explosions, the fires.

LP I talked with some American and Swiss women who studied in Switzerland in that era, and it confirms what you’re saying, that the situation was indeed different in the two countries. When were you based in Basel?

CZ I was there from 1961 to 66.

LP So you did the whole four years.

CZ Yes, I did the foundation year, and then I applied to the Fachklasse [masterclass] and was accepted. Out of 120 people, only 12 were allowed to move up into the course of study in graphic design.

LP And who was teaching in the Fachklasse? Ruder? Hofmann?

CZ It was Ruder, Hofmann. Donald Brun taught the advertising course. And we had a lot of other individuals: Kurt Hauert for design and drawing, and André Gürtler for letterform. Robert Büchler was the typography teacher, but we didn’t learn very much from him. You know, to be honest with you, it was a very non-verbal way of teaching.

LP How did you learn then?

CZ Mainly by studying work that was considered “good” in the eyes of the faculty, by observation—observation of the design work in the city of Basel and the design work on the walls of the school—and by working through lengthy, personal investigations. Hofmann encouraged us to look to the world about us. He gave impulses. The teachers didn’t talk much at all. We didn’t have discussions or conversations. We were presented with the “facts,” with an aesthetic: “This is the good way,” as if to say, “The Only Way”. Hofmann was different in that he looked into your personal direction and always gave you encouragement. He never tore you down.

LP And with most of the teachers, there was no other way?

CZ There was no other way. Modernism began in the early part of the twentieth century as an idealistic, utopian philosophy, but at the end of the movement, you will find this kind of thinking. The faithful became very, very, very stringently narrow, very opinionated. I experienced the Basel education, for the most part, as narrow-minded, defined, and controlled. However, Postmodernism’s fresh breezes were already blowing! In spite of this, I stayed, because I wanted to finish the program and stay in Europe.

LP Which teacher was the most influential for you?

CZ Definitely Armin Hofmann. His work was so fascinating, so challenging and beautiful. I think this work means a lot to us today. We need it. He didn’t talk very much. He did not preach. But he showed you. He taught by demonstrating. So we were observing what he was doing and learned that way. For instance, he told us to look at the old, traditional signs that hung over shop doors, like a croissant of metal over the bakery door, or a sword over a pub called To the Sword.

LP How about Ruder? How was he?

CZ You know, I arrived at a very bad time, when he was ill. So he was often absent. You would have to ask older graduates from the school who studied with him in his prime. For instance, Kenneth Hiebert, who created the program at the University of the Arts, in Philadelphia.

LP I am very interested in Hiebert’s work and his connections with Basel and Philadelphia. Did he study at the school in Basel before you?

CZ We overlapped. I think he was a second- or third-year student and I had just arrived. John Greiner was an American who studied at the school ahead of me. People from this time are still around: there is Hans Alleman, who taught at the University of the Arts, in Philadelphia. He’s also a graduate of Basel. Inge Druckrey, another graduate from Basel, also taught at University of the Arts. She focused on letterforms and type design. There was a bunch of us from the Basel program who taught there and made the Philadelphia program unique. Then came those from the graduate program at Basel, starting in the 1970s. For instance, my colleague and good friend William Longhauser, and Laurence Bach, who had studied photography as an undergraduate at Philadelphia College of Art. Have you talked with Weingart? Was he helpful?

LP Yes I did, and he was helpful. We had one conversation last year. He gave me a lot of information, but there was just one conversation, so far.

CZ You should pursue him, because he is the pivotal person in terms of Typographische Monatsblätter. The whole “TM Communication” series was really his baby.

LP He was very important for the period that I am focusing on in my TM research, 1960 to 90. He contributed so many articles and covers to the magazine then.

CZ That period was, I would say, especially visually rich.

LP Tell me about meeting Michael Engelmann.

CZ That was absolute fate. When I was a student in Philadelphia in the 1950s, I saw beautiful posters on Broad Street for the Philadelphia Inquirer newspaper. They were unique: large with a black background and beautiful, simple photography. I thought to myself, “This is what I want to do.” So I began researching. After two years of art school in Philadelphia, I wanted to go to Munich for a year to learn German. There something happened, by pure accident—no, by synchronicity I think I would say, because I don’t believe in accidents. I met Michael Engelmann, who designed those posters. I also met his two apprentices/colleagues, Pierre Mendell and Klaus Oberer, who were fresh graduates from Basel. They had all been taught by Hofmann. We sat down and talked. I had a miserable, little portfolio. I told them what I had been looking for, and they said, “Go to Basel, introduce yourself to Hofmann and see if you can get into the foundation year.” So I did all that and I got in. Can you believe that?!

LP Maybe, as you said, it was synchronicity! Were you there at the same time as Dan Friedman or April Greiman?

CZ No. April Greiman was a student of mine for a year in Kansas City. While in Kansas City, I collaborated with Inge Druckrey and Hans Allemann on teaching a design class. After graduating from Kansas City, April came to Basel, and stayed, I think, for a year.

LP Yes, she didn’t stay there very long.

CZ No, she did not. April and I had a good relationship while she was in Basel. Her main focus was Wolfgang Weingart’s typography class. She truly loved the experimentation. She was also the au pair for Armin Hofmann’s children. And then she went back to the US and began her design career, first teaching typography in the graphic design program at Philadelphia College of Art from 1971 until 76.

LP How about Dan Friedman?

CZ I didn’t have contact with Dan when he was at school in Basel. I only got to know him later, when he returned to the US.

LP I read somewhere that it was Ken Komai and Dan Friedman who helped Weingart to do presentations on his American lecture tours.

CZ On the initial 1972 to 73 lecture trip, I was traveling with Weingart and providing simultaneous translation. Komai and Friedman did not speak German very well at that time, and they couldn’t translate simultaneously. So I did that. Weingart and I went all over the Midwest. Ken and Dan helped Weingart on later tours.

LP I heard there was a poster made for that tour that said, “Weingart comes to America!” Is that true?

CZ Yes, and I think Komai did that poster.

LP When I read your biography, I got the impression that you moved around a lot.

CZ I was born is western Ukraine, which has nothing to do with Russia. That is very important. I grew up everywhere, so I am a bit of a displaced person or a pilgrim. I still think to myself, at 72, “You’ve lived out of a suitcase, and you are happiest when you are living out of a suitcase.” I also may have kept moving around so much because I am a war child. By some miracle, I survived, while so many didn’t. We were immigrants, my family and I. We came to the US in 1949. I think I would describe myself as a graphic designer, teacher, and artist.

LP What happened after you worked for the Halpern Agency, in Zurich?

CZ I was invited to teach drawing in the graphic design department at the Philadelphia College of Art (PCA), which is now the University of the Arts. I accepted the position because Europe went through a big recession in 1975 and 76. The agency I worked for at that time basically lost all of its clients from Germany and Austria. They couldn’t pay their employees, having lost two-thirds of their clients. Most of us were let go, so we worked on a freelance basis. I had some other freelance possibilities while looking for a full-time job, but at some point it became unbearable for me. I could just not make ends meet. It was a very difficult existence financially. At this time, in 1977, I received an offer to teach drawing at PCA. Hans Allemann, who was the head of the graphic design department, reassured me that I could teach even though I had no previous experience as a teacher.

LP It was perfect timing.

CZ Yes, but I had to come back to Philadelphia, the place I always tried to run away from. Fate and destiny. Then, after a couple of years, I was employed full-time at the college, and I began to develop the drawing program. My studies in scientific illustrations and art therapy brought new impulses, new ways of seeing and thinking. My classes evolved to become experimental laboratories where students moved fluidly between observation, intuition, and conceptual intentions.

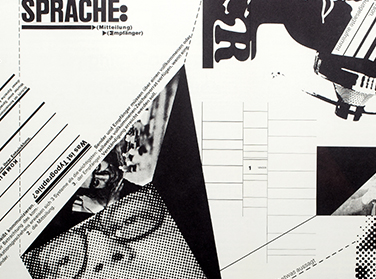

LP I’m interested in those impulses. Since I am looking at TM between 1960 and 90, I am mostly concerned with the transition that happened from Modernism to Postmodernism. Do you think those changes are related to technology only, or were they due to a change in thinking, or impulse, as you call it?

CZ For me, personally, and in the whole intellectual realm, we entered the phase of deconstruction as a response to Modernism. For me, we could now let go of stringent formulas and to begin to break through our barriers. In the time before digital imaging, visual communication began to transform because of an emphasis on photography, news reports, and the Xerox machine. Design was influenced by what was happening in fine art and vice versa. As far as digital technology is concerned, it only started being used extensively in the 90s, really. This period you are looking at—the 60s, 70s, and 80s—was relatively computer-free.

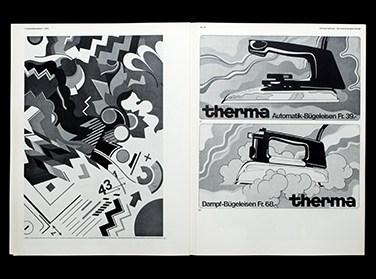

LP During the period we’re discussing, designers suddenly became more interested in the vernacular; in types of pastiche and parody, for example. Do you think that was inspired by being surrounded by fine art?

CZ I think so. I think it comes from things such as the Pop art era, the discovery of vernacular visual languages, and deconstruction philosophy. I think there was a new energy that began to push itself into the visual realm of design.

LP Because Modernism was becoming redundant?

CZ Well, it became formalistic and conceptually empty. When I look at some logo designs from the 70s and early 80s, I think, “Oh my God! How stiff and how insensitive to the meaning.” It was as if formalism had entered its last stage of atrophy. As, in life, things are born, and they blossom, and they die. And I believe that this was the final stage. But not Hofmann! He stayed “alive” until the very end of his career.

LP Maybe he was not as rigid and stuck in a formula as other designers of his time.

CZ Because he was an artist at heart.

LP Is that the recipe for good design?

CZ Perhaps. You need to stay fresh and curious. As soon as you get into a dogma, a formula, it dies.

The above conversation took place via Skype in April 2012. It was copy-edited by Ariella Yedgar and Roland Früh.